In recent decades, cities have emerged as major economic and political actors. As the world’s population is increasingly concentrated in urban settlements, cities and, more broadly, metropolitan areas have been undergoing radical transformations. New ‘urban’ conditions and challenges emerge in a fast-changing context. In parallel, for the past thirty years, the ideological domination of neoliberal austerity urbanism has entailed the neglect of underlying economic and political dynamics that shape the city and people’s everyday lives. Ironically, those responsible for strategising the city of tomorrow – politicians, planners, consultants and developers – have forgotten that cities, suburbs and satellite towns are constituted by real people with real needs, desires and motivations. Instead they promote ‘oven-ready’ policies (e.g. the Resilient City, the Creative City), incapable of creating impactful solutions to overcome the actual problems of inhabitants.

In this context, we have witnessed the proliferation of commons-based municipalist movements in various cities around the world. These have emerged as a grassroots response to the dominant urban growth model and enduring urban-capitalist crisis, demonstrating, in the words of Laura Roth and Bertie Russell, “how the municipality can become a strategically crucial site for the organisation of transformative social change”. From such a perspective, the ‘municipal’ has been taken as a privileged starting point for organising and implementing a transformative politics of scale, whilst going beyond the ‘local trap’ i.e. “celebrating the municipal, city, or local as inherently more democratic or egalitarian than other scales”, as stated by Bertie Russell in a recent academic paper. In this light, democratised, decommodified and feminised forms of municipal governance are seen as a strategic way to engage with global challenges that manifest locally.

This discussion in Greece is in its infancy. To date, there is neither an expanded, massified and translocal municipalist movement, nor an electoral platform with concrete municipalist demands. The Alexandrou Svolou Neighbourhood Initiative, a Thessaloniki-based informal organisation with municipalist aspirations, illustrates the limitations and shortcomings of institutional urban governance in Greece. This particular political and socio-cultural context is particularly hostile towards those movements that try to intervene in municipal politics. Still, I hope the following reflections contribute to a broader debate at the heart of the internationalist municipalist movement: more power to the City. Like most other contexts, it seems that Greek cities are unable to manage their urban fabric in an independent fashion. Local governments are constrained in developing decisive policies based on place-specific particularities. But we can still learn some important lessons about those limitations and the opportunities provided by neighbourhood activism, making the case for more effective and democratic urban legislative capacity.

From neighbourhood commoning to municipalist governance

The Alexandrou Svolou Neighbourhood Initiative is an autonomous activist group that was founded in 2013 in Greece’s second largest city, Thessaloniki. The Initiative is locally organised in an inner-city, highly-densified and vertically-segregated neighbourhood of the 1st Municipal District. Broadly speaking, it aims to stimulate new forms of participation through various practices of everyday appropriation and commoning, articulating a municipalist discourse on the basis of direct democracy and the collective governance of common pool resources.

Over the last eight years, the Initiative has organised concerts, parades, place-making activities and workshops, tactical urbanism interventions, memory nights, a revival of a local carnival, a picnic for the ‘global degrowth day’, initiated a network of mutual support due to Covid-19 and other solidarity actions (e.g. refugee support; for the social and solidarity economy; against privatisations). So far, the most successful projects include the organisation of a collective dinner, the biggest self-organised ‘neighbourhood fiesta’ in Greece; and the creation of a DIY Pocket Park, one of the few recorded cases of effective community-led planning in the country.

In a variety of ways, the Initiative has developed a model of direct democracy where social relations are organised around ‘place’, intersectionality and peer-to-peer knowledge exchange, without any hierarchical regulation imposed by a legal framework. This experience has introduced new elements into the discussion around the role of bottom-up initiatives in the midst of a ‘more-than-financial’ crisis, opening up new political imaginaries essential for the transformation of urban life. Such a systematic approach has generated a distinctive ‘neighbourhood culture’ and in many cases has allowed for effective and efficient group collaboration at the municipal level; yet without ensuring improved decision-making in urban-scale politics.

The DIY Pocket Park: one of the few recorded cases of effective community-led planning in Greece (Photo: Alexandrou Svolou Neighbourhood Initiative)

The role of neighbourhood activism for urban governance

The experience of Alexandrou Svolou Neighbourhood Initiative reveals some of the main administrative and bureaucratic constraints experienced when trying to intervene in the broader governance and management of the urban fabric. Overall, there is lack of transparency about local government planning processes. For example, Thessaloniki has lacked a municipal planning authority since 2014, and the planning of the city is instead dictated by the central state. The city has not developed any sort of open-source digital infrastructures that can facilitate participatory decision-making and budgeting (e.g. Decidim or Consul). In addition, as is the case in many other cities around the world, there is limited access to city archives (historical urban plans, land values, future development plans, etc.). The issue here is that there are generally no scientific publications available that are funded at the municipal level. The Greek city does not promote social research; publicly-available scientific knowledge is considerably limited.

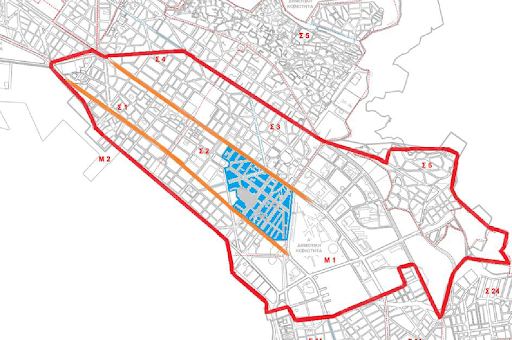

From a geographical perspective, as the research by Chatzinakos showed in 2016, it appears that the city’s administration fails to grasp the socio-cultural plurality and place-based particularities of its urban neighbourhoods. As a response to this limitation, the Alexandrou Svolou Neighbourhood Initiative has called for enhancing the administrative and decision-making role of Municipal Districts and their division into more evenly populated sub-neighbourhoods. This is related to the fact that those administrative entities are highly populated and diversified. For example, the population of the 1st Municipal District was 44.434 people in 2014.

Figure 3 With Red: the limits of the 1st Municipal District. With blue: the unofficial sub-neighbourhood of Alexandrou Svolou (Source: Municipal Department of Urban Planning & Architecture, edited by the author).

Figure 3 With Red: the limits of the 1st Municipal District. With blue: the unofficial sub-neighbourhood of Alexandrou Svolou (Source: Municipal Department of Urban Planning & Architecture, edited by the author).

Furthermore, there are cases where unused public land or assets belong to more than one public institution; sometimes these assets do not entirely belong to the city itself. For example, the Initiative is creating a DIY Pocket Park on one piece of derelict public land where 70 per cent of its total area belongs to a state-owned public limited company based in Athens. The remaining 30 per cent belongs to the Municipality of Thessaloniki. The lack of clarity over such land ownership, not only complicates those trying to intervene and improve their local neighbourhood, it also raises serious questions about the finances and rationale behind intra-governmental asset transfers.

In a similar context, there is no legal framework that supports participatory/community-led planning or locally-organised collective action for the appropriation of public space for communal use and culture (e.g. for neighbourhood fiestas). The city lacks reference points for community-building (e.g. socio-cultural centres), where residents can collectively engage in problem-solving activities or spaces that promote socio-cultural activities in public space that may reinforce capabilities for social mixing. A particularly striking example is the fact that there is no legislation regulating the creation of ‘neighbourhood socio-spatial structures’ or organisations (such as neighbourhood councils, asociaciones de vecinos etc.). As a result, residents lack opportunities to participate in local governance and collectively address the problems of their place of residence. Given this, the Initiative has proposed the creation of a municipal institution that will integrate all relevant responsibilities for the creation of incentives for citizen participation, whilst demanding that all public land be governed exclusively by the municipality.

Figure 4 The unused public land where the Initiative has created the DIY Pocket Park (in the centre), Author: Vaggelis Ameranis, The White Dot.

Figure 4 The unused public land where the Initiative has created the DIY Pocket Park (in the centre), Author: Vaggelis Ameranis, The White Dot.

Towards the city of tomorrow

In Greece, the ongoing urban-capitalist crisis has initiated major transformations, bringing with them new forms of urban living. Still, Greek cities remain both unwilling and incapable of managing their urban fabric. On the one hand, residents cannot participate in either decision-making or urban planning. On the other hand, neighbourhood activism demonstrates the limitations of urban management and local governance processes. Against the municipalist claims for more autonomy in policy-making, Greek city governments and even regional authorities have insignificant legislative capacities to meaningfully shape urban life. Greek cities require a new philosophy guiding the management of urban space.

I am not suggesting that the solution to the urban-capitalist crisis is necessarily ‘winning the municipalities’ through local elections; but after considering the limits of urban governance and the role of neighbourhood activism, is it still reasonable to argue for permanent popular assemblies and their gradual assumption of local power, challenging the fundamentally reactionary positions taken by the national government? At present, this fundamental question remains unanswered.

The answer must surely reach further than a romanticised democratisation of politics through the winning of local elections. It requires, above all, a translocal and polymorphic movement that claims more autonomy for the city, historically ruled by the central state. There is currently no movement demanding that kind of change. It also requires a new political discourse and a range of tactics, coupled with, in the words of Bert Russell, a “variegated spatial strategy of transformation” capable of establishing new collective imaginaries and ways of political participation. The city consists of a contested landscape full of contradictions, constrained by asymmetries of power, blurred class distinctions and conflicting ideologies. Only when we recognise this fact, will we be able to confidently come to grips with the full lived complexity of the new urban condition for the city of tomorrow, dismantling the state apparatus and the hegemonic form of political subjectivity. This can only happen when respective municipalist movements start to flourish, becoming important prefigurations of an emancipated post-capitalist society.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Vasilis Maggos, who died one month after he was severely beaten by the Greek police, during (and after) a solidarity demo against garbage burning by LAFARGE / AGET in the city of Volos.

Featured image: The Spring Dinner: The biggest self-organised ‘neighbourhood fiesta’ in Greece (Photo: Alexandrou Svolou Neighbourhood Initiative)