“The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights”.

– David Harvey, The Right to the City

Cities have always changed, and this change has always been driven by competing forces. Yet today, in October 2020, these processes of change have become entirely disconnected from the people who live there. Change is now driven almost exclusively by forces that are on one level utterly transparent and on the other totally opaque. You pretty much know the drill; one minute you’re passing by familiar buildings, houses and fields, and then overnight there are hoardings blocking your view. You read a post on facebook about a planning application or campaign to ‘save’ something and it starts to feel like an unstoppable machine rather than the industry that it is. An industry made up of many players, all taking their cut and all riding roughshod over local people and existing ecosystems of connections and activity.

There is no conspiracy here, rather a ceaseless march for profit that appropriates all of the value created by small business owners, their customers and local communities. A march which has created an industry all of its own along the way: developers with shareholders who want maximised profit; land agents who receive ‘finders fees’; surveyors who want high comparable rents for their landlord clients; estate agents who take an increasing commission the higher the value of the property sold; investors who want a guaranteed financial return; planning agents who are paid to push through applications; lawyers; accountants. Throw in the architects who want to make things ‘aesthetically pleasing’ in their own worldview, planners and placemaking professionals, curating from a desk far away, PR/comms firms and community engagement ‘specialists’, and you have quite a heady mix of forces.

Market Forces?

Picture the town or city where you grew up, cast your mind back and think about whether it had a market (chances are it did, maybe even two or three). Is it still there? If so, has it remained a market that serves its local community with the affordable goods and services people need – the fresh veg and fruit, the meat and fish, bread, screws, key cutting, bags, shampoo, needles, cafes, socks, guinea pig food? Or has it been demolished to make way for a newer development, or perhaps changed to some form of street food or artisan market? If you’re not sure you should Google it, but – spoiler alert – you’re likely to feel sad.

Many people will argue that this is pure sentimentality, that things change and people change with them. That you can’t stop progress. That if people had used it then it wouldn’t have disappeared. It’s just ‘market’ forces. But it is so much more than that. Across the world traditional retail markets perform multiple roles; a place of trade but also of community, a place of livelihood creation for working class and migrant peoples, a place of mutual aid and increasingly, a key site of contention in the fight for the right to the city.

These incredible ecosystems of bustle and noise, of conflict and compassion, care and commerce are massively under threat from demolition or gentrification. This leads to a narrowing of access to affordable goods and services, the marginalisation of those with less money, and the crushing of a creativity and entrepreneurialism that exists in many but only gets realised by very few.

In the middle of this milieu are municipal authorities, with their equally messy variations. Cash starved, there are huge expectations on them to deliver important services like care, education and housing. Yet (in the UK at least) they are chronically under resourced and have very little power. Within them, bodies of elected and unelected people, like with all other developments on their patch, are looking to ‘maximise their assets’ with advice from ‘retail market development consultants’. They are sold on the solution of selling public land or ‘partnering’ with developers, allegedly to bring the jobs and houses their places need, invariably by demolishing or ‘regenerating’ markets and their surrounding area.

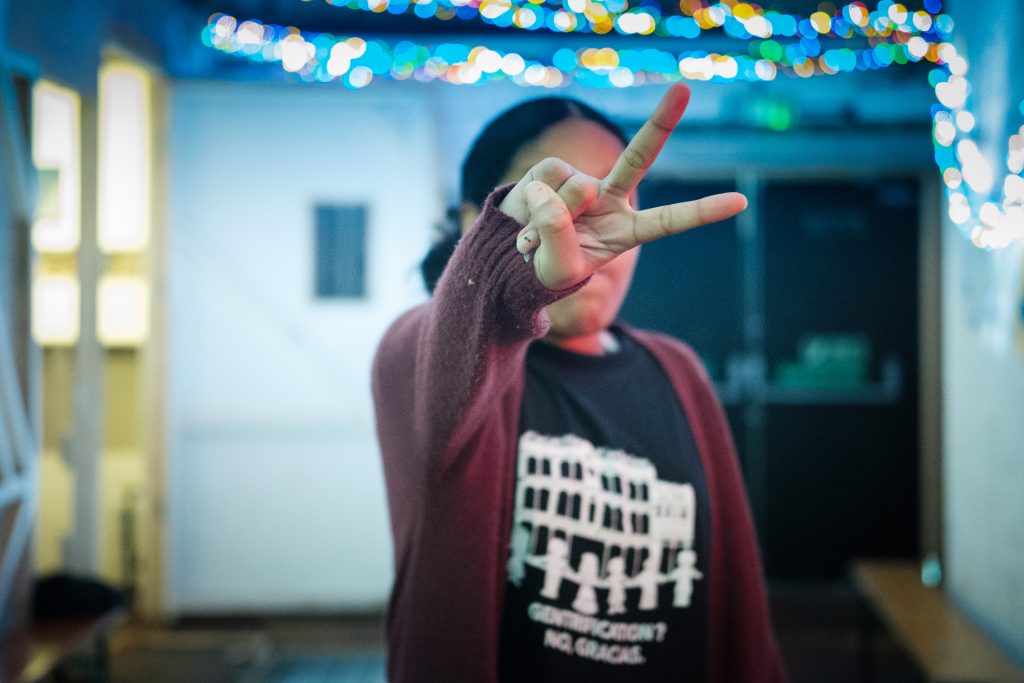

The Seven Sisters indoor market in Tottenham, London is a place of wonder. An important hub for the Latinx community in London, the market offers goods, services and a place for the local community to socialise. Filled with cafes, grocers, butchers, beauty salons, money exchange services and clothes shops, it also plays a critical role in supporting newly arrived people with legal and immigration support and translation services. It hosts 44 businesses employing over 160 people in a series of small units, with mezzanine floors based on the beauty of the ‘Pueblito Paisa’ or Latin Village. The market is a constant hubbub of conversation. Children are in their parents units or playing together on the mezzanines or in the corridors. Some evenings there is music and dancing in and around the whole market.

Housed in the shell of the Edwardian Wards Department Store, known as the Selfridges of Tottenham, the market opened in the early eighties when an enterprising local woman approached TfL to ask for a lease on the space. Having sat empty since they bought it to facilitate the building of Seven Sisters station in 1968, the high ceilings and open floor space lent themselves well to being a market. It flourished over time to become a vibrant place of community, trade and mutual aid.

Despite its vibrancy, the market has been under threat of demolition since 2003. Wards Corner had been designated in 1999 as a ‘new deal for communities’ area, a national government regeneration programme where local partnerships were established for each area so that change was ‘community led’. For Wards Corner, this programme largely enabled the local authority (Haringey Council) to appoint a developer (Grainger PLC), before selling them the council-owned Apex house for £3 million – which some may suggest was somewhat of an undervaluation. The property has now been demolished and redeveloped into two towers of 163 build-to-rent flats, with a third at ‘intermediate tenure’.

The proposal for the Wards Corner building itself is for another tower of 196 build-to-rent flats listed at market rate, with no affordable units, and with commercial restaurant and cafe units on the ground floor. This proposal is looking increasingly unviable by the day, an assertion backed up by Grainger’s own investor presentation showing this phase of the development being pushed beyond 2024. Whilst this development will now house a market (after an intervention by the Mayor of London) the provision of space is much reduced. The list of rules the developer-appointed market operator will impose will make the space a pale incarnation of its vibrant predecessor.

For nearly two decades there has been a tug-of-war between Grainger and Haringey Council on the one side, and the market traders and their supporters in the community and beyond on the other. This has focused around legal action to prevent the council from undertaking the compulsory purchase of the Wards Corner building from Transport for London (TfL), a necessary step in releasing it to Grainger. This stress of this has been massively compounded by the traders’ need to repeatedly push TfL to investigate documented claims of harassment and bullying of traders by Seven Sisters Market Asset Management Ltd (MAM), the company who held the lease to manage the market from 2015 until earlier this year when they appointed an administrator.

Partnering with community

Very early on in the campaign a Trust was established with the agenda of developing an alternative community plan for the building and surrounding public realm. This plan recognised the existing economic and social value of the market and the potential for a grassroots approach to be expanded into the empty parts of the building, providing for community, commercial and housing uses. Whilst the streets have been filled with a drumbeat of actions to prevent the loss of this incredible building and asset to Tottenham, the long-term plan has always been to try and better meet the needs of the local community. But as we see everywhere, the promise of tall glass, concrete and steel towers seems too hard for many Councils to resist, even with proven dubious benefit to local communities.

The story of Wards Corner is typical of fights going on across the world to prevent the appropriation and value capture by huge corporations and international ‘investors’. It also demonstrates the efforts of communities to preserve the culture, community and economies which grow up around people’s needs for services, goods and social contact not mediated by advertising or manipulation, but sustained through goodwill, community and connection. Others will have developed similar alternative plans which, despite being drawn up by professionals and often giving far more consideration to environmental as well as financial viability than most developer driven schemes, commonly get ignored and belittled. But these plans take time, energy and money – something campaigners lack, given this isn’t their day job, and they have to do that too. All this points to the fact that if local councils actually listened to local people and businesses in the first place, and partnered with them instead of developers, the outcomes and benefits for local people (who they are there to serve) could be very, very different.

Across the UK community led development is flourishing, with peer support networks emerging to share good practice, resources and moral support. Ranging from those with ambitions for buildings to meet a range of needs – like the community plan for the Wards Corner or Homebaked Anfield – there are also people working together to develop whole streets and even islands. This approach is now being recognised by forward thinking politicians like Steve Rotheram, the Metro Mayor of the Liverpool City Region, who has recently set up a Land Commission “to make the best use of publicly-owned land to make Liverpool the fairest and most socially inclusive city region in the country”. The aim is to develop creative approaches to the use of land through innovative processes such as Public-Commons Partnerships, which would provide a legal mechanism for Councils looking to the skills in their communities first, rather than to those from the development industry who are only looking to extract wealth and appropriate value.

This change in approach by public authorities cannot come soon enough for Latin Village and the myriad of campaigns trying to save valuable and valued community assets across the UK and beyond. If sheer determination and passion were currency we’d get further faster, but these partnerships offer hope and practical action, so we’ll keep pushing for dialogue and change, gathering momentum as we go.

Feature Image: Latin Village butchers (Photo: Mario Washington-Ihieme)