The Citizen’s Initiative Referendum is one of twelve inspiring stories of local transformation shortlisted for the 2020 Transformative Cities People’s Choice Award. Transformative Cities is a global process to search and support transformative practices and responses that are tackling global crises at the local level. You can still vote for the initiative that you find deserves more attention and resources to scale up until the 16th of November at: https://transformativecities.org.

“It’s important, for me, to speak out on this subject. I’ve lived here for almost 25 years,” explains an older woman as she signs the voters list on a windy October 2019 morning. A small group of residents, members of tenants’ rights associations and activists from the Gilets Jaunes — the so-called “Yellow Vests” social justice movement — have organized a local referendum. There’s only one question on the ballot: “Are you for or against demolishing social housing in the Arlequin Gallery?”

Mobile polling stations were set up at the 18 entrances to Arlequin Gallery, an almost uninterrupted kilometre-long collection of high-rise buildings located in Grenoble’s La Villeneuve neighbourhood, with 2000 apartments and at least 4000 inhabitants. The referendum itself had no legal basis – only local and national authorities can organize a referendum in which they choose the question. The RIC, or “référendum d’initiative citoyenne” (citizens’ initiative referendum), a direct democracy mechanism promoted by the Gilets Jaunes, aims to fills a democratic void by allowing citizens to propose to organize a vote on subjects of public interest. Indeed, over the course of a week more than 2,500 adults cast their ballot, where participation is not limited by ones nationality or citizenship status.

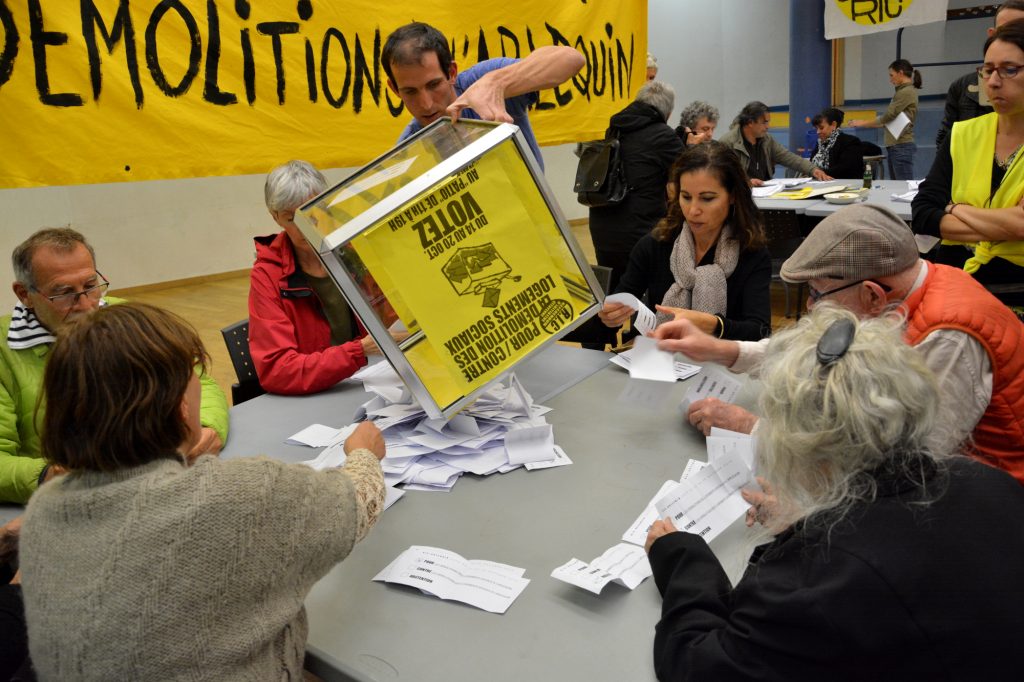

When voting ended on the 20th October, the ballot boxes were taken to a small common hall, with yellow banners hanging on the walls. “Most people did not know that parts of the Arlequin Gallery were planned to be destroyed,” deplores Thérèse Bassez, an inhabitant of La Villeneuve and a volunteer at the polling station. Just before midnight, breaking news! “526 voters. Five blank ballots. Two spoiled ballots. For: 130 voters. Abstention: 24 voters. Against: 365 voters,” announces David Bodinier, the founder of Planning, a local community organizing association.

Everybody explodes with joy. “You are officially the biggest illegal RIC in France!” shouts Raùl Magni-Berton, a political scientist who studies the RIC phenomenon.

The following day, those among the referendum’s organizers who opposed the demolition seized upon the result to demand “the end of the demolition of social housing in the Arlequin Gallery and a guarantee that the buildings will be renovated”. The city council immediately rejected the proposal and confirmed that building number 20 would be demolished, pretexting that “they are constraints with the National Agency for Urban Renewal (ANRU) which are impossible to renegotiate”. Since then, residents have resigned themselves to the demolition of building number 20, especially in the face of this lack of possible dialogue with the authorities. Whilst the demolition seems inevitable, the challenge for residents is to protect other buildings from suffering the same fate.

A long struggle

Built at the end of the economic and demographic boom of the 1960’s, La Villeneuve is now one of the poorest neighbourhoods of Grenoble. Locals say that 40 different nationalities live there, and nearly 40 percent of inhabitants are under 25. In 2016, Grenoble city council presented its new urban renewal plan for La Villeneuve.

It called for renovating large portions of the complex, but also sought to demolish other parts — including building number 20, where Virgile Gavillet has lived since 1981. “When I heard they wanted to demolish my building, I felt betrayed,” the middle-aged tiler remembers. “For years and years, we were promised that the building would be renovated. And now they want to tear it down.”

Officially, the city council and the government want to knock the building down to “create an attractive entrance to the neighbourhood in order to showcase the park of La Villeneuve”, by planting grass and some trees. But behind the demolition stand financial interests: CDC Habitat, the social housing landlord, stated that the renovation of building 20 was too expensive. For the government, the demolition is also a way to reduce the proportion of social housing in La Villeneuve.

An additional part of the plan is to be negotiated in 2021, where buildings 10, 60, 90, 110 and 120 — at least 400 apartments — are all under threat. The negotiations with ANRU, which is often pro-demolition, will be tough. The results of the referendum could show how the inhabitants of the Arlequin Gallery are attached to their buildings.

The city’s demolition plans caught most Arlequin Gallery residents by surprise. While the government is officially supposed to consult the people affected, they rarely follow through says Grégory Busquet, a sociologist from Paris Nanterre University who lives in Grenoble and studies how citizens can take action during urban renewal plans.

“The participation of the inhabitants is written everywhere in the texts of the law but, in fact, there is no participation,” he says. “The ANRU doesn’t listen to the inhabitants. It doesn’t care about the neighbourhood history, it is very technocratic.”

In Grenoble, demonstrations and petitions opposed the demolition plans, but they had little impact. This coincided with the rise of the Yellow Vests movement in November 2018, and eventually activists were demanding the RIC. The mechanism caught the interest of those who opposed the demolition, especially since Éric Piolle, Grenoble’s mayor, who said he supported the RIC the following month. Yet, when they asked the city council for help, they were rejected. “The question posed, ‘For or against the demolition of social housing?’, does not allow for an enlightened debate to take place,” the city council response reads. “Plus the project was already agreed by the councillors.”

“We wanted to do exactly what the Yellow Vests did,” says André Béranger, a long-time inhabitant of the Arlequin Gallery and a former director at the now closed down local school Les Charmes. “We wanted to give our opinion on a subject that concern us directly. The people who live in La Villeneuve do not get to express their opinions very often.”

Perfect timing

It no coincidence that the movement opposing the urban renewal plans for Arlequin Gallery chose yellow as the colour symbolizing their cause. Not only did it match the “Yellow Vests” but it’s also a symbol for the Droit au logement, a national association for tenants’ rights.

“We needed a political endorsement to bring more legitimacy to the referendum,” Bodinier from the Planning community group confides. Planning was created in 2012 as La Villeneuve were already concerned that buildings in their neighbourhood were slated for demolition.

Louise, a volunteer who lives in the Arlequin Gallery and wants to remain anonymous, spent her mornings writing down everybody’s name from some 2000 mailboxes. Others went door-to-door telling people about the RIC and debating the issues with fellow residents. Still more volunteers worked on logistics like acquiring ballot boxes. Journalists volunteered to safeguard the vote so there could be no accusations of tampering.

“The main regret I have is that there were not more people approving the demolition to organise the RIC,” Gavillet says. “The collective who prepared the referendum was rather against the demolition.”

To prevent accusations of bias, the collective organized a campaign, from mid-September to mid-October 2019, “so that residents can form an opinion on the demolition,” Bodinier says. Their goal was to make the campaign neutral and informative, and included a series of public conferences, including one titled: “Who pays for the urban renewal plan?” Attendees listed the pros and cons of the demolition and staged an open debate.

In the end, more people voted during the RIC than did in the June 2020 municipal elections five months later. “The results of the RIC show clearly that the Arlequin Gallery is a common and the inhabitants want to defend it,” Bodinier sums up.

But despite the results, the fight continues. The demolition of Arlequin Gallery building 20 now looks inevitable as the city council has refused to change plans. “There is no correct exit in this situation,” Busquet says. “It lacks a counter-project to really oppose the demolition. At the same, the RIC shows it’s possible to have a massive movement and leads to the right to the city.”

The RIC of La Villeneuve will serve as an example for future struggles in the context of urban renewal. The collective now can give tips to help organising a referendum. “I cannot believe we made it, all by ourselves, only with volunteers and without money,” says 39-year resident Virgile Gavillet. He goes on to say he is “proud to have organized the RIC”, even if building 20 is knocked down. And Gavillet hasn’t lost hope yet.

“The demolition work should already have started, but less than 10 inhabitants remain,” he says. “An eviction notice should not be long in coming. I hope I can be rehoused in the building next door. Always in La Villeneuve!”

The Transformative Cities Initiative, hosted by the Transnational Institute, provided research and reporting support for this article.

Photo Credit: Biennale Architecture Lyon