‘La olla se destapó’, or ‘the pot has been uncovered’, has become a catchphrase by which feminist activists encapsulate the biggest social and political uprising that Chile has seen since the return to democracy in the early 1990s. The unexpected emergence of large-scale protests across the country since 18th October 2019, started by high school students’ protests against an increase in metro fares, has proven effective in spreading nationwide mobilisations to fight injustice and inequality. As many placards, chants and memes have stated, this is not about 30 Chilean pesos (the increase in the metro fares), but rather “it is the result of 30 years of democracy negotiated with tear gas and 47 years of camouflaged dictatorship”, according to Alondra Carrillo, spokeswoman of the Coordinadora Feminista 8 de Marzo.

Analysts have pointed to ever-growing inequality as being at the heart of the current climate of social discontent. Various articles have addressed the fact that structural inequalities within the Chilean economic model date back to the foundation of neoliberal democracy under the economic policies of the so-called Chicago Boys during Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1990). It would be impossible to separate such a legacy from the scenes of brutal police repression against peaceful demonstrators, which includes several allegations of human rights violations, and sadly at least 23 people killed.

I want to suggest that the current wave of social mobilisations can be interpreted as the making of a feminist democratic revolution: a revolution to be made differently. The idea of the feminisation of politics, and the feminised resistances emerging from local politics have the potential to transform Chile. In contrast to how these politics have historically developed, now a new feminised practice of emancipatory politics is taking central space, through self-organised cabildos and feminist territorial assemblies, generating possibilities for building a feminist democracy and transnational networks of feminist solidarities.

Now that we are together; now they can see us

In May 2018 a feminist wave of campus occupations denouncing widespread allegations of sexual harassment at different campuses and faculties shook the country. Occupations popped up everywhere, including at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, the alma mater of the Chicago Boys, where feminist activists unfolded a banner at the front of the building with the message: ‘Let’s make the Chicago Boys tremble; long-live the feminist revolution’. Observed through a historical lens, the feminist movement (an intersection of many feminisms in Chile) must be viewed in tandem with the influence of social and political struggles led by grassroots movements, in particular by the Chilean student movement since the early 2000s. This has represented a continuous learning process, a process of re-vision, through which the feminist movement has relocated itself and its collective action within those different struggles and towards building a new meaning of ‘us’ upon which to reclaim new feminist politics.

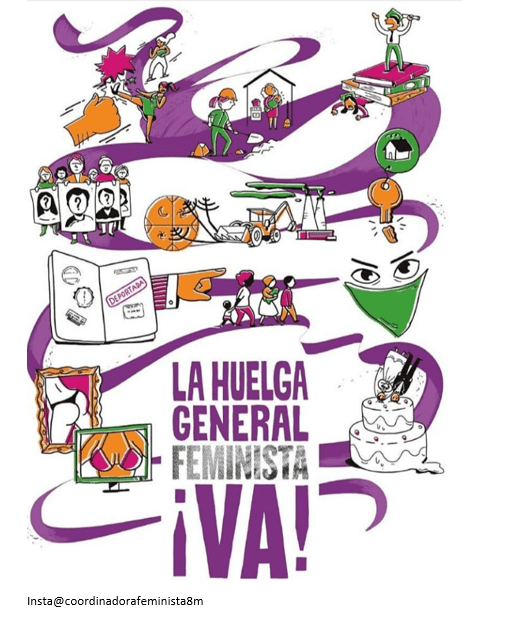

On 8th March 2019, around 1,000,000 people marched in Santiago de Chile to support the feminist general strike under the slogan: ‘Ahora que estamos juntas; ahora que si nos ven’ (‘Now that we are together; now they can see us’). In the last few years, and particularly since this historic mobilisation, feminist grassroots organisations have been in the forefront of the struggle against inequality in Chile. Today the feminist movement is the driving force behind mass mobilisations, including the historic demonstration #LaMarchaMasGrande on Friday 24th October 2019, when over 1,000,000 people marched peacefully through the streets of the capital, Santiago de Chile.

This feminist revolutionary force is also well-symbolised by the large-scale cacerolazos (banging pans protests) across the country. The cacerolazos connect Chileans with their history of resistance and mobilisations against Pinochet’s dictatorship; but they also show that the legitimisation of this political and social struggle in Chile involves its feminisation – the revaluing of political acts usually and traditionally carried out by women. Pots and pans are the explicit symbols of the kitchen and of domestic work as the first spaces where capitalism oppresses women. By bringing pots and pans to the streets and squares the feminist movement is opening up the possibility of transforming these spaces into territories of proximity and solidarity under the slogan we are all workers. So squares and neighbourhoods have become spaces for building common political horizons to transform Chile from below. Through this, a political space, where civil society can seek to articulate the possibility of building a new political imaginary of ‘we’ to reclaim their right to transform Chile from the bottom up, has emerged. This momentum offers the political possibility of broadening and deepening democracy and politics to enable the many to collectively formulate, from below, a new social contract to transcend neoliberalism in Chile. But, importantly, it also encompasses the potential of doing so through a feminist democratic revolution.

The extent to which these forms of feminised grassroot popular democratic politics could seek to transform the state while acknowledging that this democratic revolution is beyond state-structures remains an open question. For the feminist movement the current situation offers an opportunity to build a new space of autonomy as a new political imaginary in terms of how to co-exist with one foot in institutions and thousands on the streets, and most importantly, an opportunity to reassert that Chile’s democratic revolution will either be feminist or it will not happen.

Feminisation of politics

New alternative forms of doing and building politics have been at the core of the feminisation of politics. This is a practice and learning process through which feminist activists have sought to find and create common narratives of politics as a collective practice grounded in spaces of everyday life. Such practices have become increasingly important in opening up the potential to dislocate politics from the dominant hegemonic patriarchal ideas that have historically been reproduced within social movements. For example, in 2006, mass protests and school occupations led by high school students spread across the country, with demands that education be a right, not a privilege. School occupations became spaces where politics were thought, acted and experienced differently (from previous ways of making politics). Such dislocation entails not only rethinking politics as an everyday practice, but it also reimagining a different political meaning of ‘us’. A new meaning of us is reimagined through closeness, affection and emotions; as such, occupations evolved into a transformative political action of being united and no longer alone.

It is this politics of affection that allowed for the continuity of the feminisation of politics during the 2011 mass student demonstrations to demand a radical reform of the market-oriented education system. Such a politics involved a process of re-vision in which feminist student activists reimagined the possibility of doing politics in a different way and in different places. Students created territorial assemblies (or neighbourhood assemblies) as a strategy to pursue wider grassroots political alliances and politics of mutual solidarity. In doing so, territorial assemblies became spaces for building identity politics of ‘being-in-common’ – in other words politics as spaces of commonalities and proximity between different struggles. Through these spaces of proximity, student activists reframed the call for free education as a cross-cutting demand by expanding the horizons of collective action with others. In doing so, a new radical political imaginary of ‘we’ emerged to open the cage of the very first laboratory of neoliberalism by understanding that ‘we’ could also be the first ones to change this system.

The feminisation of politics has evolved to entail, first and foremost, making women visible, as well as making feminism a contested space of struggle to reclaim a different kind of politics. From the 2018 feminist wave of campus occupations until now, the feminist movement has been able to articulate solidarities and mobilisations. The widespread sharing of experiences of sexual violence both prompted the development of a common narrative and also became common places, new locations from which women could articulate a feminist politics to reclaim sexual violence as a political issue. And this feminisation of politics has the potential, as the international phenomenon of the feminist protest song ‘Las Tesis’ has shown, for a feminist democratic revolution to build a global conversation that changes the narrative about sexual violence against women, making it visible and political everywhere.

In the context of the current social and political crisis in Chile, feminists seek to centre their energy and activism on mobilising and organising through practicing politics of trust and care. The feminisation of politics has sought to reframe the meaning of ‘collective’ as denoting commonality and feminist solidarities forged in and through emotions, togetherness and a political commitment to transform Chile from below. These solidarities are also a means of reimagining, as feminists emphasise, the possibility that, when we are united, another way of living is possible, different from the one we have known until now.

Feminist democracy

The wave of social mobilisations in Chile has witnessed an upscaling of feminist democracy praxis from the grassroots level. It seeks to articulate a radical, structural, economic and political agenda that will finally overcome the continuation of Pinochet’s legacy of a neoliberal model of democracy.

To some extent such struggles are similar to those led by new municipalist movements in Southern Europe that articulate struggles for the commons, reclaiming democracy at the local level to collectively build alternatives to neoliberalism. Yet there are, undoubtedly, contextual specificities in the Chilean context.

Self-organised cabildos and feminist territorial assemblies are taking place across the country, where civil society actors meet, talk and deliberate about a number of demands on issues such as housing, health, education, pensions, climate change and a new constitution. Just as in 2011, cabildos and feminist territorial assemblies have become spaces where the feminist movement seeks to articulate a transformative agenda that is pluralist, social, political and economic. An already existing example of this upscaling of democracy from the ground can be found in local community assemblies in Valparaiso, led by a radical municipalist government. In these assemblies, there is potential as well as challenges to turn these grassroots political spaces into a critical force for building new alternative arenas of social and political change.

Plurality is key to understanding that the radicalisation of a feminist democracy relates to the possibility of co-existing with different alternatives of sumak kawsay (good way of living, according to the Quechua cosmovision). These feminist struggles do not seek a utopia of equality. As Rita Segato, an internationally renowned Latin American feminist scholar notes, they are not about claiming a bigger slice from the same cake. Rather, these struggles seek to articulate the possibility of building a society or a world, as Zapatistas claim, made of many worlds.

The extent to which movements for a feminist democracy may open the political opportunity to articulate transnational feminist networks of solidarity remains an open question. Yet struggles led by Chilean feminist activists, grassroots organisations, social movements and mobilised civil society that seek to turn dignity into common sense may contribute to mobilising a feminist dialogue and feminist solidarities on a transnational scale. A new internationalism that seeks to transcend the global hegemony of neoliberalism take shape on the political horizon only if it echoes what feminists have said very clearly: now that we are together, now they can (and must) see us.

Featured image by insta@comando_ctrl