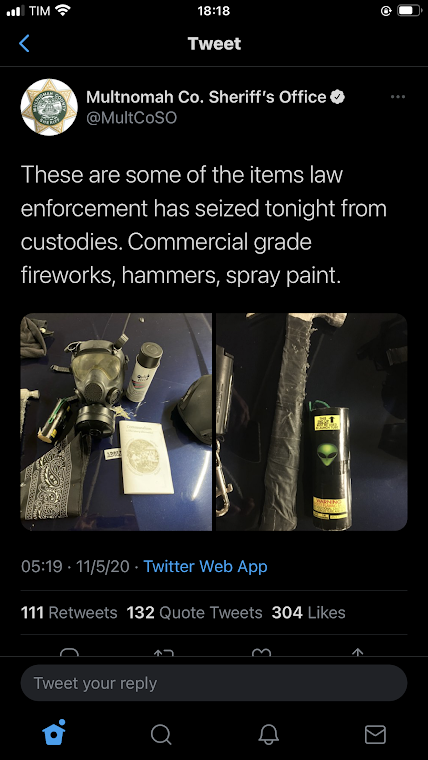

The summer and fall of 2020 brought a reckoning on racialized violence in the US at a scale unseen in generations. On November 5, in the midst of immense political tension regarding the high-stakes presidential election, the Sheriff’s Office of Multnomah County, Oregon (which contains the city of Portland) tweeted this:

The seized items — a hammer, a helmet, mace — seem hand-picked to paint the image of a dangerous rioter, someone planning for chaos and destruction. Yet among the contraband there is another, more inconspicuous ‘weapon’: a zine pamphlet. Obscured by the garish light of a police station, the cover reads ‘Communalism: democracy, decentralization, freedom, ecology”.

Why did police decide to include a pamphlet on Communalism in their display? How did the protestor come to be carrying it in their backpack? While it is useless to speculate on the intentions of police, this curious and humorous incident leads to a more interesting set of questions: In a left-leaning city where municipalist politics are perhaps at their strongest in the US, what was the engagement of municipalists in the George Floyd uprising? How do municipalists make sense of these events in their own cities?

Municipalist organizations are not immune to the dilemmas of US racialized capitalism, but they do take on a unique and valuable position. While state, corporate, and media actors work to exacerbate racialized divisions between activist groups — regurgitating tropes of “good”, docile, Black reformists in conflict with “bad”, adventuring, white “anarchists” — municipalism offers a path through these dichotomies, raising the possibility for new alliances.

The Pacific Northwest is an especially vibrant theater of municipalist organizing. It is the perfect place to look to see what happens when municipalists are on the ground as organizations and individuals on the frontlines of rebellion.

Municipalism in the Trump Era

Municipalism is a constellation of movements that seeks to reverse the flow of power in society from the top-down to the bottom up. I refer to “municipalism” here in its radical form, using “municipalism” synonymously with variations such as libertarian municipalism, communalism, and democratic confederalism. Rather than focusing on local parties and elections, these radical municipalists seek to create directly-democratic assemblies, eliminating the distinction between professional politicians and “constituents”.

Since the ascension of the far-right via the 2016 presidential victory of Donald Trump, municipalism has had a growing influence on the US radical left. Young people fed up with meaningless election cycles and neoliberal hegemony among even so-called “progressive” politicians find in municipalism a new way of imagining civic life.

The grassroots, community-driven politics advocated by municipalists also speaks to small, often-underfunded NGOs looking for more sustainable and democratic modes of organizing. Gradually, assemblies, participatory planning, and community meetings are becoming a new form of common sense.

The Pacific Northwest has become a hotspot of these kinds of grassroots, horizontal experiments. In 2017, anti-Trump protests in Seattle metamorphized into Neighborhood Action Councils (NACs) to protect neighborhoods and especially undocumented people.

Meanwhile, the organization Portland Assembly in Portland, Oregon used spokes-councils to enroll members in neighborhood associations. In neighboring Olympia, Washington, Olympia Assembly continue to organize Seasonal Planning Assemblies, where community members discuss the key social issues and problems their city.

However, in the timeframe of U.S. politics, the year 2017 might as well be ancient history. Over Trump’s catastrophic tenure, state-violence and right-wing terrorism became a part of everyday life. Life was especially dangerous for Black, Latino, Indigenous, and/or undocumented radicals who were targeted for harassment, threats, arrests, and even murder. Municipalists, like other radicals, were worn down and often on the defensive.

After years of this kind of targeting, carried out primarily by police, the summer of 2020 brought a reckoning with racialized state terrorism.

The uprising, now synonymous with the name of George Floyd, was fueled by specific conditions. A populace angry with the status quo, beset by a pandemic, was then confronted with Floyd’s murder, along with the atrocious killings of nurse Breonna Taylor, a care worker on the frontlines of Covid-19, and Aubrey Ahmaud, who was hunted down by an ex-cop simply for jogging.

White collar workers — that is, white workers —enjoyed the privilege of sequestering themselves in comfortable suburban homes. Meanwhile, service industry and other “essential” workers, who are predominantly Black, indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC), were forced to expose themselves to Covid-19, a disease they were already far more likely to die from once infected.

Without meaningful state assistance, safety networks, and even access to healthcare itself, literally hundreds of thousands of BIPOC have lost their lives to Covid-19 so far. Seen through this lens, the George Floyd uprising comes into focus not only as a crisis of public confidence in the so-called justice system, but also quite literally as a matter of survival for entire communities.

Covid-19 also led many people to become politically active and engaged.. Many people could only find personal protective equipment like masks, visors, and aprons and food through mutual aid networks. Cooperative alliances like Cooperation Jackson in Jackson, Mississippi used 3-D printing labs to produce masks and face shields at a small industrial scale. In New York City, the social center Woodbine gathered and disseminated food to thousands of the millions of people who the crisis had thrown headlong into hunger. These kinds of bottom-up, municipal-level power-building projects, who had already been active long before the summer of discontent, were able to step up during the Covid-19 pandemic. Then, when anti-racist protests escalated into open conflict with the police, they were in an even greater position to mobilize.

Seattle’s “Autonomous Zone”

In May, an uprising primarily about racial justice soon became a lightning rod for other left causes. In Seattle, overwhelmed police abandoned one of their precincts, which protestors occupied and declared an “autonomous zone”.

The initial atmosphere of the occupation, called the Capital Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) and later the Capital Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP) was celebratory. In the midst of the city’s bleak financial district, the CHAZ opened a non-commercial public realm of experimentation and play. While light barricades were erected, one street was converted into a “decolonial” café where participants could discuss tough societal issues like racism and decolonization. A garden was dug in a nearby park.

The Cooperative Assembly of Cascadia (CAC), a then newly-formed radical municipalist organization, approached the CHAZ as an opportunity to expand locally-based confederal democracy. Rather than settle for just one “autonomous” space, they argued, the movement should aim to build oppositional power in neighborhoods.

CAC was also part of a loose alliance attempting to bring a directly-democratic practice and sensibility to the CHAZ. They helped set up daily assemblies as a way to steer the increasingly chaotic project, as well as to encourage popular education in participating in a radically democratic decision-making body. Their approach was reminiscent of the horizontal, self-reflective approach to education captured by the Zapatista slogan “walking, we ask questions”.

The CHAZ experiment was in many ways inspiring, but it also fell apart due in no small part to its own lack of boundaries and responsibilities. Like many ambitious social experiments, a critical number of CHAZ participants refused to recognize “structure” or collective forms of decision-making, believing that organization itself is a form injustice and hierarchy.

Yet this very insistence of “no structure” paved the way for dominant personalities and social groups to take advantage of individual privileges, positions, and power, undermining the group’s ability to function. Feminist Jo Freeman calls this seemingly-paradoxical phenomena “the tyranny of structurelessness”.

At the CHAZ, white liberals clung to outspoken individuals of color who promoted themselves as leaders, yet weren’t accountable to any organization and were in some cases shown ot be collaborating with police and the city government. It was these individuals who “agreed” to publicly denounce radical resistance at the CHAZ and re-label the area the Capital Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP). Thus, in a sad irony, notions of “no-structure” and following “Black leadership” became the banner under which Seattle police were able to stamp out a grassroots uprising against police brutality.

The CAC were among those trying to combat destructive individualist tendencies and foster community accountability at the CHAZ. Alongside Rojava solidarity groups and others, the CAC organized sessions of tekmil; self-criticism practiced by the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), derived from Marxist-Leninism. The CAC unpack this experience at length in their recently-published collective reflection.

In our conversation, a CAC member stresses that the white myth of a morally pure Black “leadership” is a modern-day recreation the noble savage myth. Whereas whites are viewed as morally and intellectually “complicated”, BIPOC are viewed as simplistic and unified. Such myths help colonists rationalize the acceptance of single individuals to “represent” entire groups. Indeed, this process was key to the colonization of Seattle itself. As a CAC member puts it:

“When you look at the colonization of the Southern Cascadia region — what is now the Seattle area — there were once over twenty-five tribes that lived in the region. Of those twenty-five, only three invited white colonists to settle in the area. One of them was a man by the name Chief Seattle.”

Thus, municipalism in Seattle also takes the form of decolonization via alliances among organizations and movements led by and for BIPOC who are cultivating alternative, bottom-up political practices.

As an example of what this could look like, the Seattle People’s Party is a local, activist-driven party and campaigning network who are currently running progressive candidates for Seattle City Council. While the SPP frames its platform according to socialist principles, its politics are also in line with those of municipalism. They advance a platform to end homeless encampment evictions, enact wide-ranging criminal justice reforms, and embrace the Green New Deal — issues which are anathema to Seattle’s financial elite. By prioritizing social infrastructure and reforms that make civic participation feasible for society’s poor, overworked, and under-resourced citizens, the SPP remind us that there’s more than one way to define and cultivate “inclusion”, “participation” and even “horizontality”.

Any genuinely multi-racial municipalist alliance in the future will no doubt be built on such a “unity in diversity,” to borrow Murray Bookchin’s words, of groups who share values of social and economic justice and democratic self-management.

Anti-fascist alliances in Portland

In July, federal marshals and ICE agents deployed to the city of Portland, snatching protestors off the street and interrogating them in undisclosed locations. As the city erupted in defiance, liberal politicians and corporate media interpreted the city’s actions as a mere reaction. If Trump would just stop these police-state tactics, the rebellion would also cease.

When I spoke to lifelong Portland-based municipalist Tizz Bee, I found that this media narrative in effect erased a militant anti-racist alliance that had been active in Portland for over four years. The alliance has come together through years of campaigning against state and far-right terrorist violence, such as through the Don’t Shoot! movement and Occupy ICE. There’s a Portland-area anti-fascist neighborhood watch and even an antifa soccer league.

The social ecology group, Symbiosis PDX, is one actor in this ecosystem. Social ecology is a philosophy which sees real democracy, environmental health, and even natural evolution itself as intimately bound together. Its founder, Murray Bookchin, coined the term ‘libertarian municipalism’ in the 1980s to describe his grassroots, democratic political views. Social ecology is an important part of municipalist history and thought.

Established in 2018 as part of a federation of social ecology groups in the area, Symbiosis PDX eventually evolved into a member organization with dues, a charter, and individual responsibilities. Like Cooperation Jackson, Symbiosis PDX did their own manufacturing to address mass shortages of PPE, using donated industry and sewing machines. When the George Floyd uprising began, they were already organized into three “community coalitions,” each dealing with either Covid-19, the far-right’s attempted election coup, or the summer’s lethal wildfires.

The Communalism zine featured in the Multnomah County Sherriff’s tweet indeed originated from Symbiosis PDX and their summer “zine outreach”. Each night Symbiosis PDX “warrior librarians” went to the frontlines to table with literature and pamphlets while “geared out” with gas masks and shields. These warrior librarians distributed zines not only about social ecology, but also about BIPOC movements such as Cooperation Jackson and the American Indian Movement, as well as writings by the historic Black revolutionary George Jackson.

Symbiosis PDX were present at the summer’s early demonstrations outside of Portland’s downtown Justice Center. They later focused on jail support for arrested protestors. Night after night, they confronted police “in the middle of the warzone” alongside comrades such as Riot Ribs, a 24-hour outdoor kitchen led by one of the founders of the Portland Black Panthers.

Tizz Bee emphasizes the deeply personal nature of cultivating multi-racial alliances through lived, face-to-face relationships. In 2019, Symbiosis PDX mourned the death of friend Sean Armenio, a white radical who was murdered in a fight outside of a known anti-fascist building. This same community is still seeking justice for Keaton Otis, a Black youth killed in 2010 by Multnomah County police under extremely suspicious circumstances. Otis’ mother remains active in the movement to this day.

Although municipalist approaches alone are unlikely to mend the deep fissures and wounds of racialized oppression and injustice, municipalism can contribute to an organizational culture where communities of working people face state violence and fascism as communities. It retrieves our attention from the circus of national politics and corporate performance, drawing our gaze back toward one another.

Conclusion

The George Floyd uprising infused a militantly anti-racist, communal sensibility in US communities beyond the Northwest. In my home in Virginia, my mother participated in her own, assembly-like neighborhood organization. These otherwise “apolitical” suburbanites banded together to eliminate their neighborhood’s Jim Crow-era street names such as “Confederate Lane” and “Plantation Parkway”. This group was unable to meet face to face because of Covid-19, but they communicated regularly online and chatted while standing in one another’s lawns or driveways. In September, when white supremacists entered the neighborhood to vandalize the streets, my mom responded with the grit one might expect from a battle-worn anti-fascist: “They’re just cowards” she shrugged, “We’re ready for them”.

This hardly suggests the arrival of some long-awaited popular epiphany toward direct democracy. Indeed, as many commentators predicted, the Biden victory effectively cast a bucket of cold water of this summer’s flames.

But I do think it points to something one might call a “common-sense municipalism”.

With virtually all of the United States’’ social dysfunction unaddressed, we can hardly expect Biden’s balming effect to last forever. And when the next rupture does take place, we can look back at the George Floyd uprising as a clear sign-post indicating that the future of anti-racist liberation is intimate, neighborhood-level organizing — not empty attempts at national “reform” or cynical utterances that “Black lives matter” by the very corporations maintaining and profiting off the subjugation of Black, indigenous, and other people of color.

It points to a possible US where Black liberation is rightly perceived as everyone’s struggle, where being “neighbors” means fighting the state and police with a shield in one hand and a zine in the other.

All photos by Cooperative Assembly of Cascadia, except for the Twitter screenshot.