In early March 2020, as Covid-19 began to spread in South Africa, a group of community organisers, social justice activists, artists and health system researchers from Cape Town came together to plan a neighbourhood-based response to the virus and its socio-economic effects.

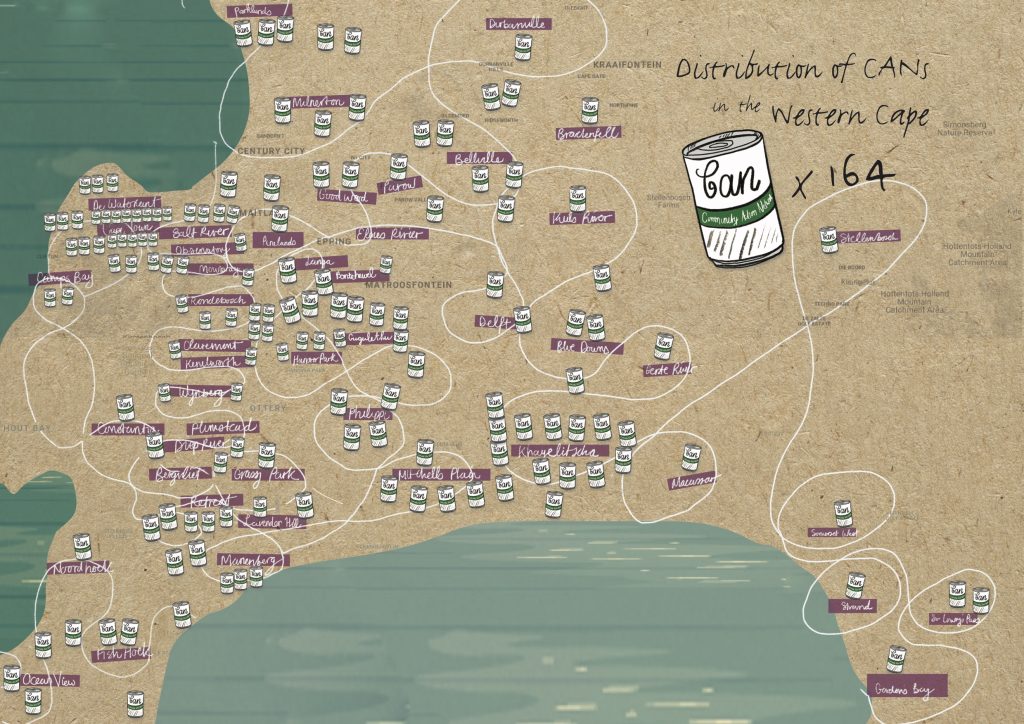

The aim of the group was to get ahead of the curve and spark an autonomous mobilisation of local civic action and solidarity that could build momentum and spread faster than the virus itself. Within days of the group’s initial meeting, Cape Town Together was born and the first few Community Action Networks (CANs) began to spring up in neighbourhoods across the city.

How the network started and grew

The model of organising was fairly straightforward. A sign-up page allowed people to enter their name, location, and contact information, and describe how they would like to contribute to the response. This could be anything from having big pots or a gas stove, a space to cook, access to a car to do deliveries, being willing to set up a local care centre for quarantining, calling people up to offer support, or simply just wanting to help.

As more people signed up, they were clustered according to neighbourhoods and connected with each other via email or WhatsApp. A small group of volunteers had worked on a “CAN Starter Pack” containing important information about Covid-19, how to work together safely in a pandemic, and some guiding principles for organising in a horizontal, decentralised and non-hierarchical way.

CANs across the city established community kitchens, responding to the widespread hunger that resulted from our hard lockdown. In addition to cooking hot meals for folks in their neighbourhood, these kitchens rapidly developed Covid-safe guidance for community kitchens to share across the network. Mask-wearing, sanitizing and physical distancing could be demonstrated in practice, while simultaneously addressing people’s immediate needs.

This was in stark contrast to the top-down public health information that was being shared in ways that didn’t acknowledge the multiple other challenges being faced. In the context of competing priorities, it’s hard to care about covid-19 when your cupboards are empty.

When it was clear that the food was running out, street corners and vacant plots were turned into community food gardens. Many CANs made plans to support Covid-19 positive people quarantining in their own homes. In some instances, where over-crowded housing made home-quarantine impossible, CANs set up community care centres within their own neighbourhoods so that people would not have to travel to state quarantine facilities in distant parts of the city.

Regular CAN co-learning sessions were held via Zoom, allowing people to discuss practical challenges facing their CANs, from how to keep a community kitchen safe from Covid-19, to navigating bureaucracies in accessing Covid-19 relief grants, among a host of other topics.

A new model, going beyond the state’s fragmented response

As case numbers rose, the strength of the network grew and, by the time we reached the peak of our first wave, there were over 170 CANs working across the city. Similar groups sprung up in Gauteng and the Eastern Cape, two other provinces in South Africa that were also hit hard by Covid-19. For many, this model of organising at the local level had an inherent “common sense” appeal.

It felt like the street-based organising that eventually became the backbone of the anti-apartheid struggle in the 1980s, of which many people still have a living memory. Given the fragmented state response, which could not keep up with the pace of the virus, let alone the second pandemic of hunger and acute food insecurity that accompanied our harsh lockdown, the CANs offered a sense of community and an opportunity to act. Moreover, it was a space without the rules, hierarchies and bureaucracy that predominate in many of the usual spaces where civic action is “allowed”.

A year down the line, some CANs have slowed down their activities – while others feel they have no choice but to carry on. The relationships are still strong, the WhatsApp groups buzzing and many kitchens still serving food, but a combination of various challenges, including immense fatigue, instances of explicit suppression by local politicians, and the difficulties related to accessing financial support without being a formally registered organisation, have slowed momentum considerably.

Building solidarity across segregation

Reflecting on a year of intense action in the face of these challenges, there are several insights from the CANs’ experience that are worth engaging with. The first insight relates to building solidarity between neighbourhoods in a city as economically divided and unequal as Cape Town. Long-lasting legacies of spatial segregation along lines of class and race require constant work to overcome.

In Cape Town Together, many attempts were made to build cross-CAN solidarity by redistributing and exchanging resources between CANs. While this did not always take the form of monetary exchange, it quickly became clear that the usual mechanisms of accounting for monetary flows between economically unequal groups clashed awkwardly with guiding principles such as radical generosity, trust-building and autonomous decision-making. In instances where exchanges were premised not on unidirectional monetary flows but rather on multi-directional flows of tangible and intangible resources – such as fact-checked information, experiential knowledge, seeds, or public statements of solidarity with other CANs dealing with violent evictions or suppression from local politicians – this was much more easily reconcilable. Of course, the re-distribution of financial resources is important in the face of gross inequality. However, it is equally important to recognise and challenge the unjust power dynamics that are too often reenforced in the process. This requires the cultivation of more robust forms of solidarity that are grounded in building trust, reciprocity and horizontality.

Avoiding bureaucracy, building lasting structures

The experience of Cape Town Together also highlights the tension and synergy between action and deliberation. An important lesson has been “a politics of doing” – as we took action together, we built the relationships needed as a foundation for the work moving forward. While being action-oriented was key to responding quickly to emerging needs, taking time for deliberation and reflection proved crucial to building momentum. As the initial panic settled into a sense of sustained crisis, and unavoidable fatigue set it, building an infrastructure for deliberation and strategic thinking became urgent. There is a significant tension between sustaining non-hierarchical movements and enabling structures for decision-making. In the CANs there were several “connecting nodes” – structures that arose in response to specific organising needs in the network as a whole. In the interests of staying away from centralised and hierarchical modes of organising these functioned in a highly flexible way, often task-oriented, and only sustained for as long as they were needed.

While the nodes themselves came and went, the inter-personal relationships that emerged from them laid an important foundation for dialogue and deliberation. Careful attention to overcoming the digital divides was a necessary starting point (and funds were raised to provide free data to anyone involved). As relationships deepened, space for dialogue opened up, and many have reflected that it is the strength of these relationships that sustain the network.

In guarding against the creep of bureaucracy and hierarchy, it was also necessary to constantly reiterate the autonomy of CANs and promote new forms of post-heroic and care-based leadership. Throughout the course of the pandemic, CAN-members were increasingly facing challenges of loss of work, illness and death within their families and communities, donor-fatigue, stress and exhaustion. The anti-hierarchical nature of the CANs, combined with a focus on creating guilt-free spaces and valuing all forms of labour (including the labour associated with caring for and supporting others) meant that all roles were flexible, and that individuals could scale-back or step out as needed. In this space, inspiring forms of leadership emerged organically.

Another society is possible

Cape Town Together and the CANs were catalysed by an unprecedented, global pandemic. This was not an attempt to bring people together under an explicitly municipalist agenda – or under any one coherent political ideology – other than a belief that local knowledge and self-organisation is best placed to respond to certain contextualities of a crisis such as Covid-Guiding principles, such as horizontality, radical generosity and solidarity across class and race lines were arrived at through praxis, rather than a theoretical or ideological positioning.

Yet, under the banner of responding to Covid-19, the CANs demonstrated a different way of doing politics at the municipal level that potentially sets the stage for extended projects in radical democracy and local action to challenge the deep-seated socio-economic inequality and spatial injustice that abounds in the city.

It’s hard to imagine how this reconciles with the inherent hierarchies in our entrenched system of electoral politics but if there’s one thing we have learned it is that networks of ordinary people doing ordinary things in an extraordinary way can be a powerful tool to demonstrate the kind of society that is possible.