On the evening of July 26th, 2018 I was at the campaign launch party for Toronto mayoral candidate Saron Gebresellassi. 2018 was a municipal election year in Toronto, and Saron, a human rights lawyer, had announced her candidacy as a campaign to build a “city where every person feels like they belong and where no one is left behind. A city that believes its poor, homeless, and working class are just as important as the rich. A city where newcomers and people of diverse backgrounds can find themselves represented in leadership and decision-making roles. A City For Everyone.”

Having just spent the last few months working with activists around the world to plan the inaugural North American Fearless Cities conference, hearing Saron’s message felt like a path towards a municipalist movement here in Toronto. In fact, in the lead up to Toronto’s 2018 election, there were three separate groups organizing in Toronto that had been inspired by the Barcelona En Comú platform that was created in 2014: Our Toronto, RadTO, and Progress Toronto. But, moments after hearing Saron speak to the crowd, Premier Doug Ford made an unprecedented announcement that he would be cutting the number of city council seats by half. Never before had a premier meddled in a city’s election, and never had the rules of an election been changed in the middle of the campaign. Hundreds of candidates across the city would now be campaigning in entirely new wards and running against opponents they never planned to oppose. The news spread quickly through the room. How could something like this even be legal? For anyone organizing on running a slate of candidates on a people’s platform, their aspirations had been cut short by Doug Ford’s heavy-handed motion.

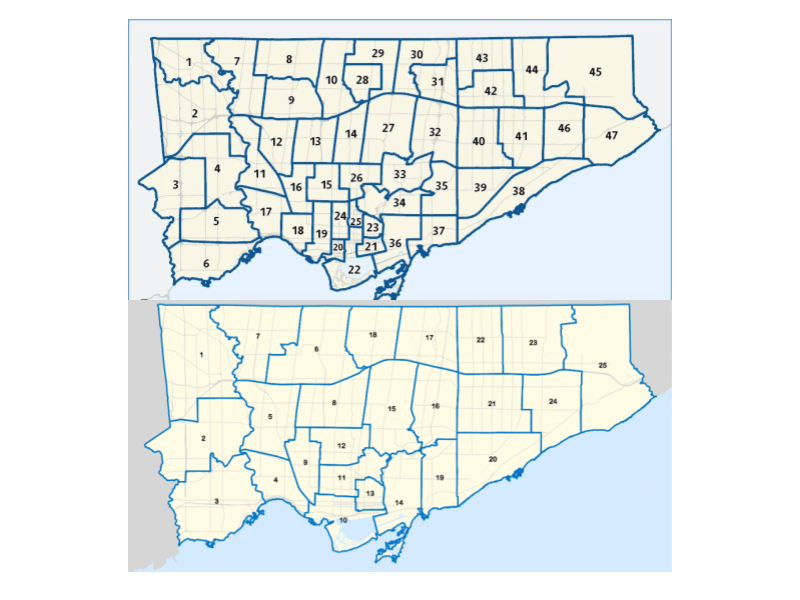

Toronto’s ward boundaries before & after Doug Ford’s decision to cut council

According to the laws that govern how Toronto can operate, the City of Toronto Act, the city must “determine the appropriate structure for governing the City […] with respect to the composition of City Council.” That should mean that Toronto has the power to decide the best way to govern the city, including how many city council seats there are.

The City of Toronto was incorporated with its own fully functioning government in 1834, a full 30 years before Ontario became an incorporated province. Yet, despite having longer tenure in governance, Toronto was considered a “creature of the province” and placed underneath the political authority of Ontario. It’s this power dynamic that allowed the Premier of Ontario, Doug Ford, to make the sidelining decision to cut Toronto’s number of city council seats in half in the middle of an election. And constraints on Toronto’s authority aren’t limited to its governance structures. In 1936 and 1944, Toronto lost the power to levy income taxes and corporate taxes, respectively, and when Toronto Mayor, John Tory, went to the Ontario Government in 2017 to get permission to propose a highway toll, to generate new monies for public transit the Premier of the time, Katheleen Wynne, rejected the petition. The city has even had its ability to manage the development of essential new transit and housing projects stripped down due to the introduction of provincial Bills 108 and 107, respectively. The city has a department of planning experts, yet, despite that, the province of Ontario has decided that it will no longer allow the actual city government to decide how to collect charges from developers, construct essential affordable housing units, or build new transit lines. With such limited authority, how could the 544 candidates who registered to run in the 2018 Toronto election, or the vast network of community organizers supporting them have any chance of making an impact on Toronto’s political future? Political changemakers like Saron and groups inspired by Barcelona’s municipalism were fighting to take power back from Toronto’s career politicians. But if Toronto’s political class couldn’t even maintain control of our political fate, how can the roots of municipalism take hold in our city hall? The answer could come in the form of a growing campaign that could fundamentally change the balance of power between Toronto and the province.

Toronto City Hall

Since September 2018, a group of residents called Charter City Toronto (CCTO), has been advocating for a constitutionally protected City Charter for Toronto. According to CCTO, the Charter would give Toronto the power to decide how to govern itself. But the Charter goes beyond just restoring the power that Toronto thought it had before, such as determining the composure of city council. CCTO also calls for Toronto to have exclusive authority for key municipal functions, control over the revenues it needs to meet its responsibilities, and ending Toronto’s status as ‘creatures of the province.’ Beth Levy, a former candidate for Toronto city council in the 2018 election, is now on the steering committee of Charter City Toronto and says that Toronto should let its own experts do the work their hired to do.

“We had transit planners who had the beginnings of a [subway] relief line that sounded great,” Beth says, “and then you have [Premier] Doug Ford come in and introduce a new subway line that planners say is never going to happen under the budget and given timelines. Then eventually somebody else will get elected, and they’ll come in and rip that up too.” Beth insists that we need to “let the planners plan, let the politicians find the money, and then get buy-in from other levels of government.” For Beth, a City Charter for Toronto is both valuable and necessary, something she says is “a tangible next step to regaining the ability to set up our government the way we see fit to.”

The next steps for Beth and the CCTO team is to build broad support for a City Charter for Toronto. Currently the Charter that’s laid out on CCTO’s website is a living document that the group hopes will expand over time as more and more communities across Toronto weigh in on what they want for the city. Once a Charter is established, the process moves to a negotiation between the City and the Province. Inevitably, for CCTO to have the long term municipal protection, it will require an amendment in the constitution. Something that could prove difficult with a provincial government that isn’t willing to cooperate. CCTO is working on building broad support with major parties and across all levels of government.

I asked Beth if she remembered when she got the news about Premier Doug Ford’s decision to cut council in half in the midst of the 2018 election. “I was really excited about the election and the candidates that were running,” she told me, “Toronto is poorly represented, but that year we were really on the path to have more women elected, more people of colour. The LGBTQ community is going to get more representation. And then July 26th came and all of these fabulous people either dropped out or were pushed out so they didn’t have to run against the incumbents.” The new changes meant that Beth Levy would now be running against Mike Colle, a longtime political incumbent who she knew would win. “I stayed in the race,” Beth said, “but I just knew it wasn’t going to happen.”

For Beth, working in CCTO is the way to get Toronto to a place where inclusion and diversity are again a possibility. She says “if people from diverse communities can see that their voices matter, then we can change the makeup of city council, which can then change the lens from which we look at everything the city does.” This could help get Toronto to a place where political movements, such as municipalism, can take root. With two more years until the next municipal election in Toronto, building broad support of a City Charter is the best way forward for anyone hoping to bring the idea of municipalism to the forefront of our local politics.

Featured image: mayoral candidate Saron Gebresellassi during the electoral campaign in 2018

Photo: BlogTO